The U.S. Congress has recently heard a report from the House Judiciary Committee which presents disturbing allegations about U.S. Government involvement in surveillance and censorship focused on citizens’ social media activities. The report raises concerns about breaches of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment guaranteeing freedom of speech. Something highlighted by the report is the role played by University of Washington academic, Dr Kate Starbird.

The attention this has drawn to an individual academic has been condemned in the press as politically-driven and unwarranted harassment. In the Washington Post, Naomi Nix and Joseph Menn (2023) refer to a ‘deluge of bad information about disinformation researchers’ work’ that ‘has led to a torrent of digital harassment’. That concern has been shared by a number of academics who see it also as an indirect assault on academic freedom.

I shall offer a different perspective. In 2020 I wrote an article criticising Starbird’s academic work for alleging disinformation without evidence. My article was peer-reviewed and accepted for publication – but never published. The editors told me this was due to pushback on multiple fronts. So, who was pushing back? How did they come to have influence over the editing of an apparently independent academic journal? At the time, I could only speculate, but the new revelations supply tangible evidence of how the academic world is being captured by what is aptly called the Censorship Industrial Complex. My own story, thus, opens a little window onto a much bigger – and very disturbing – picture. It is, as we shall see, a picture in which both freedom of speech and academic freedom are being eroded.

My initial story, in brief, is this. In January of 2020, Kate Starbird, with her PhD student Tom Wilson, published in the Harvard University journal Misinformation Review an article called ‘Cross-Platform Disinformation Campaigns: Lessons learned and next steps’. The article’s opening foregrounded the claim that it would help ‘conceptualize what a disinformation campaign is and how it works’ (Wilson and Starbird 2020). On reading the article, however, I found their opening claim to be misleading. For the article offers no word of advice on how to identify disinformation and, therefore, leaves radically unclear how one might identify a disinformation campaign. I made this point in a reply article that I submitted to Misinformation Review. After being peer-reviewed, the reply was accepted for publication. The editors also notified me that, because it presented such a direct challenge to Starbird’s work, the journal would invite a rejoinder from her to be published alongside it. Several weeks passed. I then received a very apologetic email from the editors telling me that unfortunately the publication would not go ahead. This was a disappointment to them too, I was told, as they had devoted a ‘considerable amount of time and care to shepherd the manuscript through our workflow’. But the fact was, they had encountered ‘pushback on multiple fronts’.

I could understand the difficulty that Starbird would have in addressing the criticism that she was condemning some people’s communications as disinformation without explaining how that verdict was arrived at. For she plainly had been, as I described in the unpublished article (which can be viewed on my blogsite here). But were the editors of Misinformation Review now reversing their decision to publish for that reason? It would be highly unusual and unprofessional for a journal to allow one author effectively to veto the publication of work by another. In fact, the editors’ letter had referred – rather mysteriously – to pushback on multiple fronts. So the recent revelations in the U.S. Congress offer intriguing – if also disturbing – intimations of who may be some of the stakeholders with an interest in avoiding academic attention being placed on the basic problem with Starbird’s work on ‘disinformation’.

The main interest in this case, then, is ultimately less about an individual academic than about how academic positions and reputations can be instrumentally leveraged in pursuit of ends that run counter to the fundamental functions and responsibilities of a university in a free and democratic society.

Starbird’s Role in ‘countering disinformation’

Starbird’s particular academic research trajectory has developed closely in line with the direction of U.S. policy-makers. In her position as Associate Professor at the University of Washington, her research has been funded by government grants since 2013, and from 2017 through 2020 she was awarded more than $1 million in federal grants from the National Science Foundation (Benz 2022). She is also the Director of Washington University’s Center for an Informed Public (CIP) which was launched in 2019. The Center has wealthy and influential supporters – to date, it has received funding of about $6.5 million from sources such as the Election Trust Initiative, Microsoft, Omidyar Foundation, Knight Foundation – and in 2021 it was awarded a $2.25 million grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) ‘to apply collaborative, rapid-response research to mitigate online disinformation’ (CIP 2021).

Starbird has powerful connections, as was evident when, in December 2021, she was asked by Jen Easterly, the director of the US Government’s Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), to serve on its external advisory committee (CSAC). Starbird was also to chair a subcommittee referred to as ‘MDM’ – an acronym used to refer to ‘misinformation, disinformation, and malinformation’. With Starbird on this subcommittee were Vijaya Gadde, who at the time was head of legal, policy, and trust at Twitter, Brigadier General Alicia A. Tate-Nadeau, and Suzanne Spaulding, a former CIA legal advisor ‘who at the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) had a rank equivalent to a four-star general, managing a $3 billion budget and a workforce of 18,000’.

CISA is an agency of the DHS, which, as its original 2002 mandate — the war on terror — was wound down, had pivoted to monitoring social media and was ‘quietly broadening its efforts to curb speech it considers dangerous’ Klippenstein and Fang (2022). Although CISA’s ostensible focus is on cybersecurity and infrastructure, its definitions and terms of reference have been persistently stretched to include ‘disinformation’. Easterly has rationalised this with the argument that ‘we’re in the business of critical infrastructure, and the most critical infrastructure is our cognitive infrastructure, so building that resilience to misinformation and disinformation, I think, is incredibly important’ (Easterly, speaking at a conference in November 2021, quoted by Klippenstein and Fang (2022). CISA meetings would be attended by senior executives from Twitter and Wall Street, where they would hear from the FBI ‘that the threat of subversive information on social media could undermine support for the U.S. government’ and that ‘we need a media infrastructure that is held accountable.’ Klippenstein and Fang (2022)

Starbird’s MDM advisory subcommittee was created as a replacement for the Countering Foreign Influence Task force that had been set up in 2016 to process the – since discredited – RussiaGate allegations. It was intended ‘to promote more flexibility to focus on general MDM’, (Cuffari 2022, p7) which meant including domestic as well as foreign communications. In June 2022 MDM produced a report that called on CISA to closely monitor ‘social media platforms of all sizes, mainstream media, cable news, hyper-partisan media, talk radio and other online resources.’ They argued that the agency needed to take steps to address the ‘spread of false and misleading information’, especially information that undermines ‘key democratic institutions’: ‘Pervasive MDM diminishes trust in information, in government, and in the democratic process more generally. … The spread of false and misleading information poses a significant risk to critical functions like elections, public health, financial services, and emergency response.’

Behind the scenes

A study of this report during its drafting (with accompanying emails) is instructive. The report opens by citing a ‘growing body of research’, including Starbird’s own, which establishes a definition of disinformation as ‘false or misleading information that is purposefully seeded and/or spread for a strategic objective’. According to this definition, any instance of disinformation could be demonstrated by identifying how the information is either false (as innocent misinformation can be) or misleading (by making use of demonstrably deceptive selectivity of truths). Yet as was seen in the article of Starbird’s that I criticised, this is not what her research does. Nor, it appears, is it what she is necessarily recommending that CISA should do. For a problem that the report highlights as a major concern for the agency is one that does not involve misinformation or disinformation, according to those definitions, but, rather, is presented by ‘information that may be based on fact, but used out of context to mislead, harm or manipulate’ [my emphasis]. I here emphasise the word ‘used’ because the information itself is not false or misleading. What Starbird, thus, acknowledges in this report, which she avoided mentioning in the article I criticised, is that a significant part of her concern is with something that – despite what she had said in print – should not be called disinformation at all. This distinct concept is instead referred to as ‘malinformation’.

It is interesting to note that even her fellow subcommittee members pressed the obvious concerns about the implications of lumping this in with actually false or deceptive information. In communications about the draft report ahead of its presentation to CISA, Spaulding raised concerns about deploying this concept. She does agree ‘it could fit the kinds of risks we are concerned about. The challenge may be that because it is not false, per se … it is much trickier from a policy perspective.’ Spaulding suggests that they compromise by keeping malinformation as part of their scope but focus recommendations primarily on countering false information. Starbird, allowing this, emphasises that they do need to keep malinformation in their purview as it is one of the ‘most effective tactics’. Nevertheless, she accepts Spaulding’s suggested compromise for the purposes of the report. Hence the draft report retains ‘MDM’ in its opening paragraph whereas all the further references in the document have been discreetly replaced by ‘MD’.

Starbird and her colleagues on the MDM group were aware that their activities were liable to arouse public concern if known. So the report was edited with that in mind. On 19 May 2022, Starbird emailed the other members of the MDM Subcommittee: ‘I made a few final changes this morning and … I removed “monitoring” from just about every place where it appeared. I made a few (2-3) other defensive word changes/deletions.’ When asked if they should cite some studies in support of a claim they were asserting, Starbird replied that, although initially having included some, she had decided to remove them ‘because each citation/example seemed to open up an opportunity for an attempt to undermine our work (since everything is politicized and disinformation inherently political, every example is bait).’ (Email from Starbird 14 May 2022, screenshot in Judiciary Report, p.10)

They were further aware, as Spaulding emailed Starbird on 20 May, that it was ‘only a matter of time before someone realizes we exist and starts asking about our work.’ She urges Starbird that they should ‘find time to talk with CISA comms and legislative folks about how we socialize what we’re doing. It would be good to be proactive in telling our story rather than reacting to how someone else decides to portray it, right? And I’m not sure this keeps until our public meeting in June.’ (Screenshot in Judiciary Report, p.31) Starbird replied ‘Yes. I agree. We have a couple of pretty obvious vulnerabilities.’ The advice they received back from CISA was that they could think about ‘socializing’ the existence of the group among ‘key stakeholders’ but without giving any particulars about its work (email of 26 May attached to CISA’s draft report). Apparently in this connection, Starbird mentioned a ‘Columbia law professor’ and a ‘George Mason law professor’.

The public concern

It is clear, then, that Starbird understood that the work of her subcommittee had to be rather artfully presented for public consumption. At the heart of its vulnerability to scrutiny was a readiness of Starbird and colleagues in practice to include ‘malinformation’ alongside misinformation and disinformation in order to flag as problematic the full range of messages they aimed to investigate. Examples of such practice were revealed in emails from the ‘Twitter Files’ that showed how the Virality Project, run by the Stanford Internet Observatory (SIO), in partnership with Starbird’s CIP, had been actively collaborating with Twitter to suppress information they knew to be true (Adamo and Joner 2023).

The concept of ‘malinformation’ is profoundly problematic. When developing any kind of policy with regard to it, major questions are who decides when a use of undisputedly true information is harmful, and on what basis? Regarding the ‘who’, given that the MDM subcommittee is part of a DHS agency, it is not surprising that those they regard as stakeholders and who influence their objectives include people associated with the security state, other government departments and Wall Street. On the question of ‘when’, Starbird has an alarmingly expansionist view. Consistent with her tacit admission that one of the most effective ‘tactics’ she would have government power deployed to disrupt is the publication of inconvenient truths, she explicitly floats the view that hacked or leaked materials should not be presumed to have the legal and constitutional protection of ‘speech’ within democratic norms. This would mean that any whistleblowing or revelations comparable to the Pentagon Papers or Watergate, for example, would be deemed ‘malinformation’ and, thus, ‘dangerous to democracy’. In effect, any kind of serious investigative journalism could then not be protected under the First Amendment. Regarding the basis for deciding when true information is ‘dangerous to democracy’, no explanation is offered. It does so happen that some thinkers have offered justifications, in principle, for silencing ‘toxic truths’ or promoting ‘noble lies’, yet these are inherently controversial and arguably incompatible with fundamental principles of liberal democracy (Hayward 2023). So their application to any particular case is likely to be contentious, to say the least.

Concerns about the arbitrariness of criteria for designating a communication as ‘malinformation’ are compounded when its distinction from misinformation and disinformation is effaced by its being packaged into a supposedly single problem telegraphed with the acronym MDM. For then information that is true can be referred to under the same heading as information that is false or deceptive. MDM potentially includes any information whatsoever that a group like Starbird’s simply declares it does.

This is essentially the problem I highlighted in the article on Starbird that was suppressed due to ‘pushback on multiple fronts’. That article attended to just one instance of what has now been revealed to be a far greater concern in light of the report by the House Judiciary Committee.

The response of Starbird and her supporters

Starbird has responded to the House Judiciary Report, in a blogpost (Starbird 2023), that it ‘contains many inaccuracies and creates false impressions about me, my research, and my participation on an external advisory committee for the Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA)’. The alleged inaccuracies turn out to be interpretations of the evidence in the Report that she finds challengeable. The concerns I have outlined above relate exclusively to what she and her collaborators have themselves written. Her response does not address those concerns.

Starbird makes no attempt to defend her work on ‘malinformation’. Instead, near the start of her response, she appears to want to distance herself from the controversial MDM conflation when she explains ‘MDM is an acronym that the government uses to mean Misinformation, Disinformation, and Malinformation’ (my emphasis) – as if she herself had not been actively advocating its inclusion in counter-disinformation efforts. She now carefully describes the remit she accepted from Easterly as being to recommend ‘how CISA should approach the challenges of mis- and disinformation’, without mentioning the word ‘malinformation’, even though Easterly’s brief that Starbird quotes from repeatedly refers to MDM.

What Starbird more explicitly distances herself from is any suggestion that the MDM group’s advisory role had any operational element. Indeed, the report she is replying to covers operations affecting the 2020 election, before the MDM group was formed, which involved another group sponsored by CISA that Starbird had also been part of. The Election Integrity Partnership (EIP) was jointly run by Starbird’s CIP and the SIO, and included the Atlantic Council’s Digital Forensics Research Lab and Graphika. Alex Stamos of SIO headed the EIP, and he stated its purpose was ‘to try to fill the gap of the things that the government could not do themselves’ because ‘at the time CISA lacked both the funding and the legal authorizations’. He told the New York Times: ‘we have had two-way conversations with all of the major platforms … Facebook, Twitter, Google, Reddit … our goal is that if we’re able to find disinformation, we’ll be able to report it quickly, and then collaborate with them on taking it down’. Starbird herself was evidently acculturated to this way of working, as in 2020 when she was expressing concern that Twitter was ‘too slow’ in labelling tweets as misinformation: ‘Mostly things take off so fast that if you wait 20 or 30 minutes’ she said, ‘most of the spread for someone with a big audience has already happened”’ (Culliford 2020). Clearly, she did not intend that careful analysis should be made of the tweets but, rather, snap decisions should be made on the basis of a set of pre-agreed triggers.

Nevertheless, a line of argument advanced by Starbird’s supporters is that there is just nothing wrong with what she has been doing and that the critics’ position is unreasonable. The Seattle Times sets the tone by referring to Starbird’s activities as those of ‘a group of private and public research groups that receive tips about misinformation, which they forward to tech companies to handle as they wish’ (Dudley 2022). Professor Jeff Hancock – [a leader at Stanford’s end of the EIP](https://cyber.fsi.stanford.edu/news/225m-funding-national-science-foundation-help-support-mis-and-disinformation#:~:text=The National Science Foundation (NSF,research to mitigate online disinformation.) – argues they have ‘freedom of speech to tell Twitter or any other company to look at tweets we might think violate rules’ (quoted in Myers and Frenkel 2023). Jameel Jaffer, a Columbia Law professor, goes along with this: ‘There’s nothing at all nefarious about researchers studying online speech and sharing their conclusions with social media platforms — and this activity is indisputably protected by the First Amendment’ (Kaminsky 2023). This judgement appears to treat the ‘advice’ element provided by Starbird, no matter how enthusiastic for results she may have been, as entirely separable from actions actually taken by collaborators to censor information. Jaffer, incidentally, is a member – along with Starbird, Stamos and former CISA director Chris Krebs – of the ‘Commission on Disinformation Disorder’ at the Aspen Institute.

If some of her supporters downplay the concerns about the activities Starbird is party to, others turn on the people voicing the concerns. An example from another professor appears in Crooked Timber – a left-of-centre political blog run by academics that, according to the New York Times, could claim ‘a reputation as an intellectual global powerhouse’ (Paul 2011). The political scientist Henry Farrell writes that ‘The claim that these academics are part of a “government-approved or-facilitated censorship regime” is complete bullshit.’ He says he has personal acquaintance with Starbird, and also her Stanford partner Renée DiResta (formerly of the CIA and a leading advocate of government-funded internet censorship (Shellenberger 2023)), which has given him ‘a sense of how they think, and what they are doing.’ This, he explains ‘is why I’m writing this post.’ He singles out an article in The Intercept by Klippenstein and Fang (2022), that I have cited above, for chastisement:

‘The Intercept piece not only stinks, but has become the foundation for a much bigger heap of nasty. … It’s an article whose fundamental flaws have caused specific hurt and had wide repercussions for American media and politics. Fixing fuck-ups like this is Journalism Ethics 101.’ (Farrell 2023)

Unfortunately, he does not specify the flaws nor clearly indicate what needs fixed. The hurt he refers to would presumably be the social media reaction Starbird experienced in the wake of the adverse publicity, which would of course have been unpleasant for her, but is not due to any journalistic shortcomings Farrell has been able to identify. As for the wider repercussions, the argument could be made that Klippenstein and Fang have done exactly what is needed to try and lift the quality of public debate and discussion in support of freedom and democracy.

Meanwhile, the response of mainstream media (e.g. in The Guardian, New York Times, Washington Post) has been to avoid discussing the wider issues raised and instead to cast the story in terms of a right-wing campaign to hamper legitimate research. It is true that the Judiciary Report was produced by Republicans, and that several law suits, including a class action law suit citing Starbird, Stamos and DiResta, are being coordinated by supporters of Donald Trump (Bokhari 2023); it is also the case, however, that requests to the University of Washington (UW) to release documents relating to Starbird’s activities with CISA have been intercepted by the Biden administration’s Department of Justice, as documented by Lee Fang (2023). The fact is, information requests to UW have come from left-leaning groups as well as from the right (Piper 2022).

For there are issues here of fundamental constitutional importance. If some academics are not greatly perturbed by targeting information favourable to Trump, the point should perhaps be emphasised that freedom of speech is expressly intended to protect the expression of opinions you disagree with. The point also applies to the censorship promoted by the Virality Project, which used a supposed public health justification for taking down social media posts. The censorship applied even to posts containing true information if they used keywords from any of the ‘narratives’ proscribed on the grounds that they undermined public confidence in the public messaging authorised by congress – many of whose members received donations from the pharmaceutical industry.

Nevertheless, the defence of Starbird’s specific role has mainly centred on claiming it is protected under academic freedom. Her EIP colleague Hancock maintains that their activities represent a legitimate exercise of ‘academic freedom as researchers to conduct this research’ (Myers and Frenkel 2023). This issue merits closer attention.

Academic Freedom

A presumption that Starbird’s activities with CISA, the EIP and the Virality Project constitute legitimate academic work has certainly gained currency in some quarters. It animates a line of thought that the Seattle Times Editorial Board captures when it declares that ‘Starbird and other scholars shouldn’t have to face political bullying. Professors are used to defending their work, and engaging in debates over theories’ (Seattle Times 2023). There will be others, of course, who are less convinced that projects whose core activities include instantly taking down social media communications on certain politically sensitive topics really serve the advancement of science or scholarship. But I shall focus on a challenge to the invoking of academic freedom in defence of Starbird that is more directly related to the academic element of her work.

The case I narrated at the start of this article, directly from my own experience, relates to work of Starbird’s that is describable as academic, since it is presented in an academic format in a peer-reviewed publication. Yet the case showed Starbird precisely not to be engaging in activities that the Seattle Times rightly understands to be protected under academic freedom. For in response to my academic criticism of her work, Starbird did not attempt to defend it or enter any debate. Rather than exercising academic freedom, she was declining to engage in the process that the principle of academic freedom exists to protect.

Now, Starbird’s supporters might argue that she is under no academic obligation to engage with every criticism that her work might attract. This is fair enough, at least on the assumption that others enjoy the academic freedom to evaluate the criticism themselves if they find prima facie merit in it. Yet precisely this exercise of others’ academic freedom was precluded in the case at hand. For interference in the process of peer review by non-academic pressures caused the reversal of an editorial decision and blocked publication of criticism of Starbird. This precluded the possibility of anybody exercising academic freedom in relation to the suppressed material.

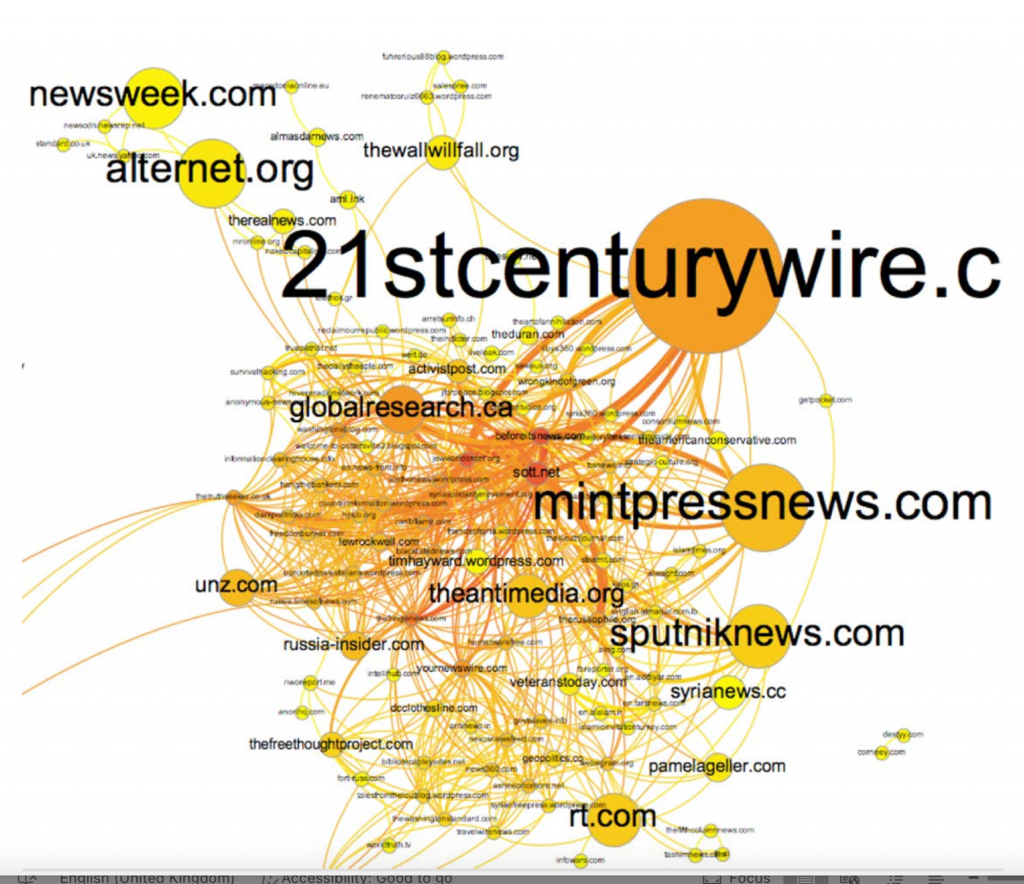

What the suppression of my criticisms shows is that academic freedom was sacrificed to the cause of maintaining a government-approved narrative. Those criticisms related to Starbird’s work on a project completed prior to her involvement with CISA, but they highlight the same core issue – the branding of inconveniently true information as ‘disinformation’. In her report to her government funders on that earlier project, she depicted dissenting opinion as Russian Disinformation. Yet I know as a matter of certainty that this is a spurious depiction – not only because she makes no attempt to show any of the communications monitored to be false or deceptive, but also because she fails to demonstrate any coordination by Russian agencies. I can be certain about this because in a domain network graph depicting a cluster of internet domains supposedly purveying Russian Disinformation, I find – in small letters but right in the middle – my own WordPress site.

According to the theory Starbird presents, this makes me ‘deeply integrated’ into an ‘echo system’ whose ‘underlying structure — a seemingly diverse, but interconnected set of websites … can create a sense of false triangulation … somewhat resistant to claims of orchestration — at least from a surface perspective that fails to recognize the underlying mechanisms of information shaping.’ Yet her assumptions about those ‘underlying mechanisms’ invert facts about the direction of influence. The fact in my own case is that the content shared was generated by me and picked up by others: this post, for instance, was reproduced or linked to by 37 other sites, this by 39, and this by 59. The site showing in large writing on the graph, 21st Century Wire, reposted seven of my articles.

Starbird’s construction is premised on a conspiracy theory of ‘orchestration’ that is straightforwardly falsified by such facts – with mine being by no means an isolated case, as shown in my original critique of Starbird. The methodological laxness is such that she has not even attempted to rule out the alternative explanatory hypothesis that clusters of independent sites converge on a certain perspective because it is an epistemologically robust one. If that convergence also happens to suit Russian interests to cite, this might just mean you can’t disbelieve everything Russians say.

Academic work exhibiting the methodological failings just highlighted cannot withstand proper academic scrutiny – as the fate of my suppressed article on it implicitly confirms. But it evidently suits the purposes of the US government in stigmatising inconvenient truths as ‘Russian disinformation’. This was implicitly confirmed with the further funding awarded to Starbird to continue such efforts via the EIP and Virality Project. In this connection, it is also relevant to note that around the same time as Starbird was engaged in that earlier project, a shadowy UK operation called Integrity Initiative, applying similar methods, was flagging a tweet of mine, while also generating farcical media allegations that Twitter accounts of, for instance, a Syrian chemist in Australia, a retired businessman in England, and a world famous concert pianist were Russian bots (Macleod 2021) – just because they dissented from mainstream narratives.

This was the work specifically of Ben Nimmo. Like Starbird’s, it was evidently appreciated by U.S. Government, as Nimmo went on to become head of investigations at Graphika, a company receiving multi-million dollar funding from U.S. Government departments (Shellenberger 2022, p.14) and partnering with Starbird in the EIP and the Virality Project. These projects, in turn, are part of a wider programme involving a nexus of operators straddling academia, government, ‘civil society’, and the media who coordinate to take down inconvenient communications in a ‘whole of society approach’ to ‘disinformation’.

This could potentially account for the fate of my own earlier academic scrutiny of Starbird which the Misinformation Review editors told me received ‘pushback on multiple fronts’. That journal’s editorial board, as my own initial experience with editors showed, includes plenty of diligent academics, but it also includes Renée DiResta – Starbird’s EIP and Virality Project partner – whose name features so prominently in Shellenberg’s testimony to Congress. The journal and its host, Harvard Kennedy School’s Shorenstein Center, have meanwhile been at the centre of public controversy over problematic ascriptions of ‘misinformation’ (Smith and Matsakis 2023). Also perhaps worth noting is that the Shorenstein Center’s collaborator at Harvard on its Democracy and Internet Governance Initiative is the Belfer Center: this is directed by Eric Rosenbach, a former Army intelligence officer and Department of Defense Chief of Staff, with the former CISA director Chris Krebs as a senior fellow and Starbird’s MDM partners Spaulding and Stamos as advisers.

Whatever the exact source(s) of the pushback, its result was to prevent wider scrutiny of the academic component of Starbird’s activities. Starbird was left free to ignore critical questions and to refrain from engaging in the activities of open debate and discussion that others rightly see as essential to academic work. Nor can Starbird be regarded as simply a passive beneficiary of the pushback. For, as we have seen, she privately demonstrated awareness of ‘vulnerability’ to the core criticism, and, rather than address it, she opted to deflect it – including by branding those making it as the bad faith actors. She has offered no acknowledgement of how the issue bears on her published academic work, offered no correction to it, and appears to have uncomplainingly allowed academic criticism of it to be suppressed.

In view of these considerations, it seems to me that academics who attack Starbird’s critics might do well to refocus their righteous indignation. There is a clear public interest in knowing the basis of ‘academic’ advice that is directly used in the restricting of others’ channels of communication. Requests for documents relating to this do not infringe on academic freedom, since the genuine exercise of that freedom inherently involves making public the results, workings and assumptions of research. If documents that are subject to information appeals are of an academic nature, asking to see them should not be problematic or objectionable.

As for communications between individuals with academic positions and non-academic bodies about non-academic matters, these can legitimately be subject to freedom of information requests. Public expectations of transparency in the conduct of ‘impactful’ academic work are entirely reasonable. It cannot be considered intrusive on academic freedom to hold to account those actively involved in recommendations of specifically targeted censorship of fellow citizens’ communications.

Conclusion

The instrumentalising of academic reputations – institutional and individual – in the service of interests other than the advancement of knowledge and understanding appears today to be an inescapable reality in a world where research is often funded by organisations with vested interests. If this is an especially significant issue in the field of ‘counter-disinformation’ research, that is not surprising. Such research is invariably directed to topics of substantial interest to influential funders including Big Pharma, Big Tech, Wall Street and the Military Industrial Complex. The flood of government funding into this newly contrived research field is already starting to shift normative baselines within academia. The uncritical uptake by others of work like Starbird’s is just one illustration of how methodological standards can be eroded.

Conscientious academics have a clear professional and social obligation to resist this process. At the very least, they should in their own work strive for sufficient awareness of it to avoid uncritically citing results based on demonstrably flawed methods and assumptions. This is a standard obligation of academic diligence, but it needs to be taken especially seriously when the historical record is being directly shaped by publications funded in the service of one-sided agendas.

The role of a university in a democracy is to support the generation and dissemination of the most reliable knowledge possible; citizens rely on universities to support high standards of public debate. It is incumbent on academics to support the raising of the quality of public debate, rather than succumb to the downward pressures imposed by those who want to restrict public debate to areas that do not criticise powerful interests. The risk at present is of the quality of academic publications being pulled down by practices now being encouraged by ‘counter-disinformation’ funding.

(Featured Image: “1A0A8477” by Knight Foundation is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0. Cropped by Propaganda In Focus.)