Introduction

Michelangelo mastered mannerism, Georges Seurat pointillism, Vincent Van Gogh impressionism, Edvard Munch expressionism, and Pablo Picasso cubism. The multiplicity of movements developed by countless other masters throughout the ages have often been motivated by the spirit of the age in which the painters, sculptors, filmmakers, and musicians work. While romance and love, for example, have moved men to launch a thousand ships, man’s general inhumanity toward his fellow man has also provoked some of the most astonishing visual interpretations of the world. Guernica, that modern icon of revulsion of fascist wartime violence, may quickly come to mind.

All forms of fine art are abstractions from the deeply felt experiences people register, find virtually ineffable, but are nonetheless moved to share their understanding of. While some forms, such as Andy Warhol’s “Campbell’s soup cans”, approximate more realistic impressions of the vacuous practice of pointless mass consumption, others appear to signal an effort to represent and integrate the subconscious world with the material. For example, if psychoanalysis was Sigmund Freud’s attempt to probe and describe the innerworkings of the subconsious mind, surrealism became Salvador Dali’s graphic response — a twentieth-century literary, philosophical and artistic movement that explored the workings of the mind, which underscored the irrational moments of that age.

John Whitehead’s work, in a similar vein, plumbs the subconscious minds of people in the present age. In particular, they are the technocrats, assorted sycophants to social power, and investors in the 4th Industrial Revolution — the New World Order of social relations crafted by the demands of the current corporate-government nexus erecting “a kinder, gentler” façade for fascism in which “more concentrated, unscrupulous, repressive, and militaristic control by a Big Business-Big Government partnership preserve[s] the privileges of the ultra-rich, the corporate overseers, and the brass in the military and civilian order.” Approaching Whitehead’s work is akin to donning the special shades that filter out the all-encompassing mediated world, obscuring the view of most characters in John Carpenter’s 1988 classic, They Live. Survival, for Roddy Piper’s character, depends on recognizing reality and struggling against Keith David’s, to don the shades and to actually see the horrors of the empirical world. Whitehead seems to dare us to do the same.

After earning a terminal degree (MFA) at the San Franscisco Art Institute (SFAI) in 1981, Whitehead had an epiphany that stripped away the dominant simulations peculiar to the social world of that time. A revulsion at the mostly shallow and tawdry work of that era, framed as fine art, sent him on a jouney into a wilderness of self-reflection and some time to see what he could truly see beyond the art world’s pandering to neoliberal postmodern pretentiousness. With forty years in practicing his craft, Whitehead has since been cultivating a particular approach to the canvas which he calls “humanistic misanthropy” — a synthesis of various schools, the most obvious being impressionism, expressionism and surrealism. Since the JFK assassination and the ensuing sideshow Warren Commission inquiry, all of which annihilated his youthful naïveté, he has since observed with careful skepticism the long parade of outrages offered up by the corporate media — from “Iran/Contra, Oklahoma City bombing, 9/11, the Iraq and Afghanistan misadventures to the current blockbuster, Covid Biotech Military Industrial Pharmaceutical Totalitarian Pandemonium Final Solution”. He has used them to shatter and reconfigure the simularcum in the interest of achieving a pure and undefiled form of brute honesty.

If human beings manage to survive this present epoch of technocratic global shock in tact, Whitehead’s renderings may well go down in the annals of art history as some of the most prescient documents of the controlled demolition. Apart from Whitehead, hardly anyone else appears on the scene nowadays to be committing to canvas such raw truths in acrylics, pastels, and oils. Whitehead’s work may be a preferable scene to behold since so much art worthy of serious note is so often just a rank regurgitation of the vapid mass culture that incubates it. This essay, the first in a limited series on John Whitehead’s work, offers analysis of the visual representations the artist has developed for those who are alert to the unfolding confluence of political power, technocratic incompetence, and plutocratic narcissism.

A Full Palette of Styles

If the pen is mightier than the sword, the brush, for Whitehead, is a ballistic missile. Style, form, subject, perspective, and color are given intense consideration and one cannot help but give Whitehead’s attention to detail corresponding levels of contemplation. The paintings deliver honesty with shock and awe. Even a momentary glance at any canvas should apprise the viewer of how deftly the painter invokes and reinterprets most of the notable schools of 20th century art, each piece appearing to be a clever contemporary nod to expressionism, impressionism, fauvism, surrealism, pointillism, and mixed media collage.

The subjects that Whitehead treats have tended over the years to focus on nature and the natural order: disturbances to peace and serenity, to landscapes defiled by “progress” as well as to members of the faceless masses constrained, manipulated, or conquered by the foul, degenerate forces behind “friendly fascism” parading itself, at present, with a wink and a grin and the promise of some “safe and effective” “medical” upgrade.

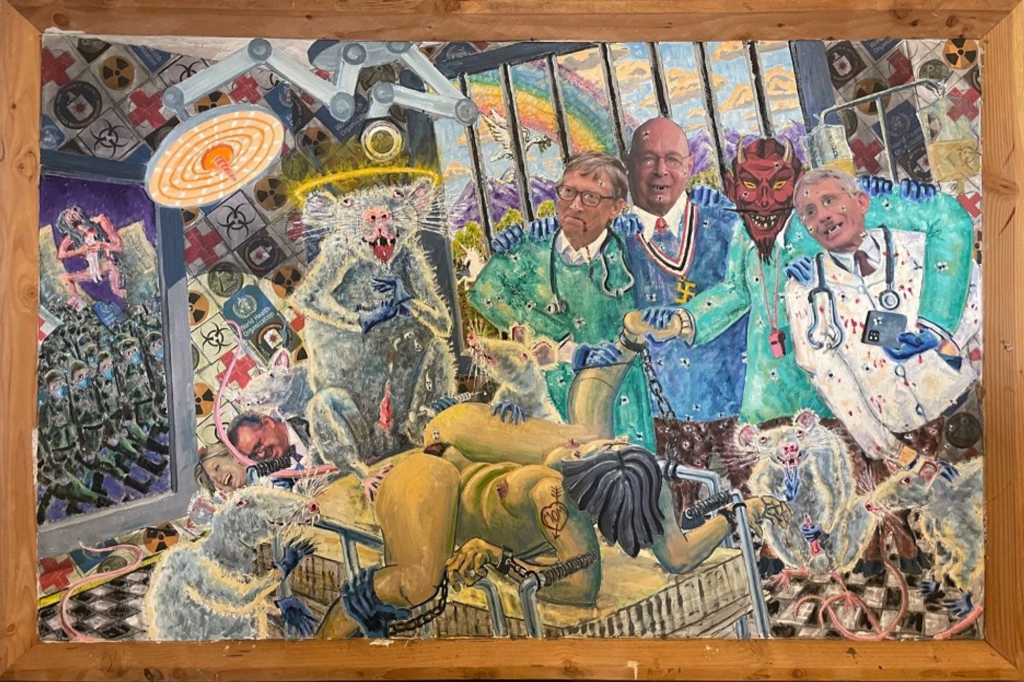

Regarding perspective, Whitehead prods viewers of “Leda and the Rats”, for example, to peer into the operating room of some techno-utopian hospital where the leading investors and generals of a new kind of Trojan War, waged against the flesh and the psyche, are tending to an operation in progress. The usual suspects leading the current technocratic global order appear to look on — embraced by Beelzebul with one hand in the rape-torture and the other with mobile device ready to snap a group selfie of the procedure. It is the present base audaciousness of the whole biomedical simulacrum that seems to motivate this particular rendering.

Whereas William Butler Yeats had synthesized myth and history in his sonnet “Leda and the Swan” where the young maiden is bathing nude, is overpowered and penetrated by Zeus (in the guise of a swan), which ultimately leads to war, Whitehead synthesizes contemporary life in the foreground with the weapons of the Pharmaceutical Empire, backed by The Science™, arrayed against a naked young woman, chained to a hospital gurney, who is about to be violated by a menacing rat.

As the technocrats envision themselves as cool and detached hyper-hygenic saints of the new world, the hideous white lab rat — long an object of both revulsion and abuse in larger industry experiments — is elevated to the position of holy subject and given a halo and freedom to reign over the object of experimentation. Bizarre ironies abound in the rodent, the conventional vehicle of disease spread, now fitted with requisite rubber gloves and scheming with deranged and unbridled excitement, visible in a reference to Munch’s “The Scream”, to spread his seed — each droplet seeming to be aware of something too sinister and revolting to speak.

The rape of the woman depicted here is, in so many ways, the rape of so many human beings “locked down” and constrained psychologically by the agitating drone of fat-cat technocrats whose marching orders for humanity have resounded incessantly in the mainstream media echo-chambers since 2020, urging “normalcy only returns when we’ve largely vaccinated the entire global population”.

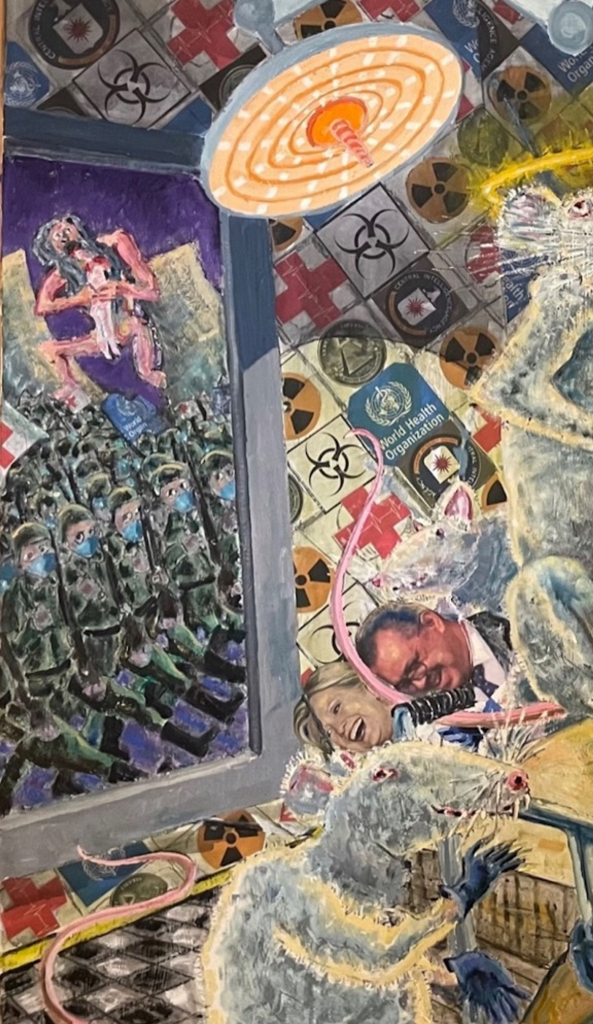

Featured, also, in the OR is a window frame through which an impression of Francisco Goya’s rendering of Saturn (Moloch) can be seen striding between two nuclear cooling towers and appearing to survey columns of surgically masked fascists goose stepping before him while he devours the corpse of a baby. Decorative wallpaper festooned with the leading symbols of the present age serve as the backdrop.

On another wall, in the background lies the Garden of Eden, visible but unapproachable behind the solid bars that separate the material world from the sublime and undefiled. A rainbow of all seven colors, a blue sky undefiled by aerosol injections from passing aircraft, and natural cloud formations all form an image in the memory of many before the New Normal was rolled out. “Purple mountains majesty” appear to signal a time before Manifest Destiny colonized the world in the name of “progress”.

Stripped of her natural female identity, agency, and sovereignty, the woman in this present day and age is being erased from memory, dispossessed of her autonomy to reproduce, raped by technocrats and their medical experiments, “people with the capacity for pregnancy,” and cancelled by the “influencers” of contemporary culture to assert her natural rights to protect her bodily integrity. All of the psychopaths and minions of temporal power confront the female attempting to protect herself from the threat of a larger, perverse culture bent on total control over her natural female form and powers of reproduction.

Populating the OR are more lab rats and other forms of parasitic infestation (cf Lord of the Flies) excited by anticipation to join the official violation. This new kind of stealth warfare against women is characteristic of the present global struggle for human rights but which may be most shocking to those who see themselves as inviolable creatures of a benevolent Creator.

Conclusion

As the contemporary world, guided by the captains of transnational finance, have funded the invasion and occupation of nearly every living thing, John Whitehead has mounted a significant defense with brush and canvas, throwing to the wind all of the pretensions of false politeness and has laid bare the depraved world remade in the image of the architects of this global order of horror. They claim the system works: it’s why they have to blot out the sun. The system works, they say: It’s why they have to infuse the air with nano-toxins, aluminum, barium, yellow fungal mycotoxins, cadmium, and polymer fibers. They claim the system works: It’s why pure drinking water must be adulterated with the externalities of heavy industry. Since the mainstream mustn’t know too much about these forms of pollution, it’s why the civil right to free speech must be curtailed.

The system, they insist, works: it’s why the human right to decline participation in medical experiments must be destroyed. It’s why we must return to streams and meadows to find sustenance and shelter, fire for cooking, and all the necessary instruments to maintain domestic life. It’s why they propagate their investments in lab-grown meat, insect flour, and cockroach milk. They must return a profit.

John Whitehead dares his audience to stand up and examine the vast expanse of this profound medicalized insanity, to not turn away from the image of the world the technocrats are now making for a global population that “will own nothing and be happy”. “Leda and the Rats” asks us, “can you not yet see what’s really going on with these coerced interventions?”

(Featured Image: “Defibrilator Paddles” by Tim Reckmann | a59.de is licensed under CC BY 2.0.)