Researching and writing about propaganda can be tricky. It is not particularly popular amongst mainstream academics who sometimes become tetchy when confronted with the notion that propaganda is alive and well in liberal democracies. Acknowledging that powerful actors pour huge resources into managing the ‘information environment’, in order to manipulate perceptions, attitudes and behaviours, tends to play havoc with assumptions underpinning much of liberal political science. Bringing propaganda into the frame risks opening a can of worms and messing up elegant models purporting to explain how politics and society work.

That said, the last four years have seen the emergence of a more widespread acceptance of the fact that propaganda is very much a part of our world. The COVID-19 event, more than anything else, has mainstreamed its discussion. In particular, the use of behavioural scientists and the use of fear-mongering have been major components of efforts by authorities to instil fear of a virus and organise the conduct of populations. At the same time censorship, which is a central component of propaganda campaigns, is rampant. High profile scientists have been de-platformed by ‘big tech’ whilst, as the Twitter Files have confirmed, US federal agencies have interacted with social media companies in order to censor alleged ‘disinformation’. Tim Hayward’s recent analysis of the massive “NewsGuard operation”, for example, is one among many others triggering a vigorous response from scholars. Things have become so bad now, we even have a new term to describe our Orwellian conditiont — the ‘Censorship Industrial Complex’.

It is reasonable to surmise that, as awareness of propaganda has grown, so too has the harshness with which powerful actors pursue their attempts to manipulate and control. Most likely there is an interactive process at work. As powerful actors push harder to persuade and control, populations become more aware that they are being manipulated, and this then leads to even more repressive propaganda tactics being employed. Such an escalatory dynamic might explain the recent emergence of various censorship regimes across liberal democracies, under the guise of online safety legislation, many of which are premised on the fallacious idea of protecting us from ‘harmful’ ‘disinformation’.

Propaganda becomes most aggressive, in the sense of leveraging a person’s material or physical well-being, when it enters the realms of incentivisation and coercion, whereby threats become part of the persuasive process. One very obvious example of coercive propaganda relates to the case of Julian Assange, editor of Wikileaks. Currently held in Belmarsh Prison under threat of extradition to the US for publishing secret information, Assange’s real ‘crime’ has been to help reveal the brutal reality of the West’s global ‘war on terror’ in countries such as Afghanistan and Iraq. The British and American authorities’ ‘propaganda of the deed’ here revolves around making a clear and brutal example of Assange, one that will intimidate whistleblowers and any journalists challenging the crimes of their governments.

These harsh, nefarious, and destructive approaches to suppressing dissent include the tactics of character assassination and smearing. These tactics are accurately understood as a form of propaganda in which the objective is to influence beliefs and conduct by destroying the reputation of an individuals or organisations. This might start with unpleasant legacy media reports unfairly attacking the credibility of a person or organisation and then shift into a coercive legal realm, as we have seen with Julian Assange. In between these two poles lie attempts to destroy a person’s material well-being by having them fired or, in the case of independent journalists, demonetised. All of this, of course, remains one step short of murder, the ultimate method of silencing critical voices and a tactic which, unfortunately, is not unheard of. Character assassination and smearing are more commonplace than most people realise. US journalist Sharyl Attkisson’s The Smear provides an insider account of this method whilst The Routledge Handbook of Character Assassination provides an academic rendering. Character assassination and smearing are key components of a propagandist’s tool kit.

The plight of Professor/Dr David Miller is a case in point. Fired from the University of Bristol in 2021, Miller was a well-established and influential professor of sociology known for his work on propaganda and its role in the exercise of power. I have co-published with Professor Miller and together we have been involved both in the study of propaganda during the 2011-present war in Syria, via the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media, and have sought to encourage and facilitate academic work on propaganda via the Organisation for Propaganda Studies. His ‘crime’ was to have become caught up in the study of the Israel-Palestine conflict, with a particular focus on the politics of Zionism and the networks of government linked entities that work hard to promote its agenda. Of course, the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is deeply controversial. As I write, we are witnessing a global debate with respect to the actions of Palestinian resistance groups on October 7 and the Israeli government response. This is only the latest phase in a conflict that began over 150 years ago with the first Zionist settlements and which then escalated with the Nakba in 1947/48. We are witnessing everything from mass protests through to UN General Assembly resolutions on the crisis, and there is clearly much support for the Palestinian cause. And the longer the fighting goes on, the more it becomes clear that Israel, supported by its allies in the West, is engaging in an act of Genocide against the Palestinians.

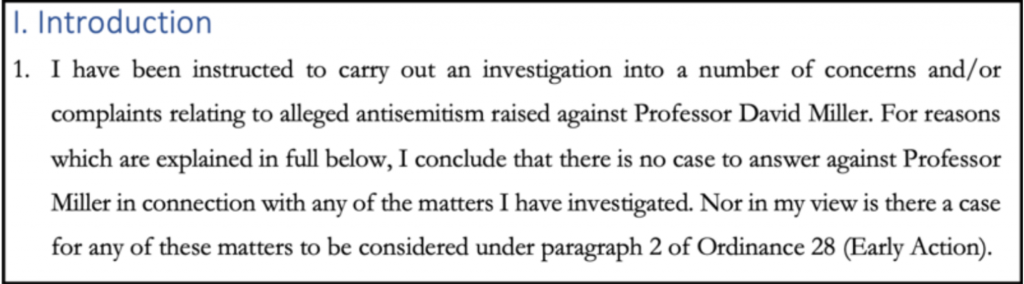

The starting point for Professor Miller’s ordeal was a lecture he gave in February 2019. Drawing upon his work on both Islamophobia and the Zionist lobby, as well as his extensive work on propaganda, Miller described to students how Zionism is one driving factor in promoting Islamophobia. This resulted in him being targeted by pro-Israel groups and individuals who accused him of antisemitism. The subsequent complaint against Miller was rejected by the University of Bristol in an internal judgement in June 2019 and then again at the end of 2020 when a KC appointed by the University reached the unequivocal conclusion that Miller was not guilty of antisemitism.

Exert from report by KC (King’s Counsel):

In early 2021, Miller critiqued a decision by University College London (UCL) to adopt the IHRA (International Holocaust Remembrance Association) antisemitism definition. This controversial definition allows a wide range of commentary critical of Zionism and the Israel government to be designated as antisemitic. The deleterious consequences of the IHRA definition for academic freedom, and freedom of expression more generally, are clear. They create an environment that stifles legitimate debate and criticism with respect to both Israel and the ideology of Zionism. In making his critique, Miller referred to his own experience at Bristol of having been targeted by the Bristol Jewish Society and the Union of Jewish students, both of which he identified as “formally” Zionist groups because of their affiliation to the World Zionist Organisation. Although cleared once again by the KC of having said anything that was antisemitic or constituting harassment or discrimination, the University of Bristol fired Miller on the grounds that his comments in relation to students and student societies amounted to gross misconduct. An industrial tribunal at which Miller’s case for unfair dismissal is being considered. What is already clear, at least to any objective bystander, is that Professor Miller has been subjected to a relentless character assassination campaign to smeared him as antisemitic and which was successful in having him removed from his post. It continues to this day.

Miller’s experience serves as a paradigm case study of the reality of researching propaganda, coming up against powerful vested interests, and then being targeted by smears and character assassination drives. There are many others. My own experience, with which Miller is connected through co-published research, concerns the investigation of UK government sponsored propaganda operations during the war in Syria. A number of us established the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media in early 2018 and one of our concerns was with the chemical weapons allegations being made against the Syrian government and the accuracy of OPCW (Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons) investigations into these alleged attacks. As soon as we established this group we were hit with smeary blog posts and then malicious media reports and tendentious editing of Wikipedia pages. In fact, we were pasted all over the front page of The Times of London, smeared as ‘conspiracy theorists’ and war crime deniers’, just as the UK, US and France launched strikes against Syria in response to an alleged chemical weapons attack in Douma on the 7th of April 2018. The smears continued even after testimony from whistleblower scientists within the OPCW emerged to corroborate our research. The scientists were also then smeared. Of course, what we quicky realised, as soon as the attacks started, was that we were ‘right over the target’. We had poked a large and sophisticated UK government propaganda operation designed to facilitate ‘regime-change’ in Syria. We now know a lot about this operation, have much of it documented, and will continue to research and write about it in the coming months and years.

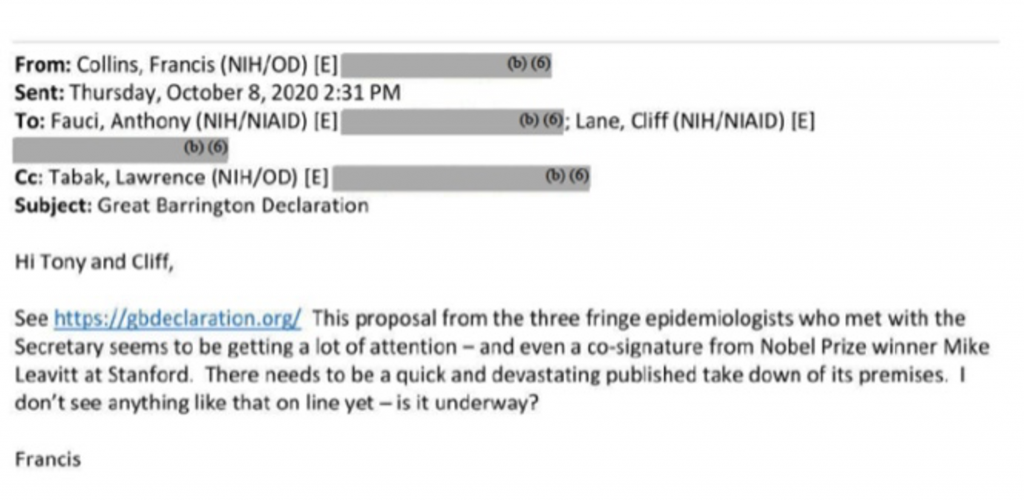

Away from the realm of foreign policy and war, the COVID-19 event has seen many scientists, researchers and doctors being smeared, de-platformed and even fired for questioning official narratives. The most prominent example of smearing is that of the Great Barrington Declaration and its lead scientists Professor Jay Bhattarcharya (Stanford), Sunetra Gupta (Oxford) and Martin Kulldorff (Harvard). Published during Autumn 2020, the declaration reflected an assessment, shared by many scientists, that lockdown strategies were not a rational response to Covid-19. Rather than engaging in a civilised, sensible, and objective debate, the head of the National Institute for Health, Francis Collins, emailed Anthony Fauci, Chief Medical advisor to the White House, smearing the scientists as ‘fringe’ and asking when a ‘quick and devastating published takedown’ would be prepared. In the ensuing storm of media criticism, for example, Professor Gupta was smeared as a conspiracy theorist and also instructed, prior to an interview with the BBC, not to mention the Declaration. Other academics during the COVID-19 event have lost their jobs.

Email from Francis Collins to Anthony Fauci:

In an earlier era, when scientists and researchers questioned the official narrative regarding 9/11, they were similarly smeared, and some were fired. Specifically, Kevin Ryan was fired from his job at Underwriters Laboratories when he spoke out about its investigation into the building collapses in New York on 9/11. Professor Steven Jones, who tested dust samples from the World Trade Center collapses and found evidence of thermite explosives, was forced from his position at Brigham Young University. When the late Professor David Ray Griffin expressed doubts about the official 9/11 narrative, the then corporate media journalist Tucker Carlson smeared him as ‘blasphemous and sinful’ on live television.

What we have today is not new, then, although the use of character assassination and smearing has probably become more widespread. The first important lesson to learn from all this is not to be discouraged by the existence of these tactics as this is precisely what those in power are seeking to achieve. It is reasonable to assume that the attacks on Julian Assange, the so-called ‘rogue academics’ working on Syria, and the authors of the Great Barrington Declaration, were intended to set powerful examples to anyone else asking difficult questions on these important matters. Likewise, the campaign against Professor Miller was more about using the firing of a high-profile Russell Group University Professor in order to deter others from researching the Israel/Palestine conflict than it was about the ‘problem’ of one Bristol University Professor and his lectures. The lesson to be learned, instead, is to recognise this tactic for what it is, and to then develop ways of pushing back.

Once one has recognised a character assassination campaign for what it is, a deliberate and carefully thought through propaganda campaign, it becomes easier, psychologically at least, to stand your ground. Part of this should involve avoiding being drawn into adopting a defensive stance, in which you attempt to counter every single little smear. It should be remembered that smeary labelling tactics — such as ‘conspiracy theorist’, ‘war crimes denier’, ‘anti-vaxxer’ — are forms of ad hominem, a fallacious argumentation tactic: the attacker avoids engagement with substantive factual analysis and discussion by discrediting the victim through making false, misleading, or irrelevant claims about their character, identity, or psychological makeup. This does not constitute reasoned debate and dialogue. Rather, the response should be to stay focused on the facts at hand and to continue to robustly put forward your analysis and evidence. Keeping on this track can succeed in countering attempts to put you on the run and to cause you to deviate from the substantive issues at hand.

Another important lesson to keep in mind, as you battle through character assassination and smear campaigns, is that their existence means you are on target. Recognition of this should encourage you to have confidence that you have hit upon an important issue and one that those in power are desperate to suppress. The more severe the attacks, the more important the issue is. As part of this, it is also worth keeping in mind that if you are not getting attacked, then you are not doing your job. As Professor Michael Parenti pointed out when discussing the failures of mainstream journalists to effectively challenge power:

They say, ‘are you telling me that I’m not my own man … I always say what I like. And I say to them: you say what you like because they like what you say. And you have no sensation of restraint on your freedom. I mean you don’t know you’re wearing a leash if you sit by a peg all day.

In short, studying propaganda effectively requires the researcher to endure the roller coaster ride of smears and character assassination campaigns.

Of course, playing it safe, or being ‘tactical’, is understandable, especially for academics in prestigious institutions. But to do so for fear that a smear campaign might be initiated against you results only in a victory for those seeking to suppress public awareness of an important issue. For serious analysts of propaganda, it means undermining your own research agenda. A little bit of thumos — the Greek spirit of the inability to tolerate an injustice without taking action — is what is required, as well as the recognition that, in the grand scheme of things, you are doing the right thing.

In the final analysis, as Francis Bacon wrote, ‘truth is the daughter of time, not of authority’. This is certainly the case with respect to the examples discussed here. Professor Miller stood his ground, suffered, but now we see an unprecedented level of global support for the Palestinians; part of this increased awareness is because of Miller’s courage. The Syria chemical weapons issue is still discussed at Security Council level, and now even with the Brazil government raising the issues set out by the whistleblower scientists. The scientists pushing back against the COVID-19 event now enjoy the backing of a substantial globally networked resistance. And the work of those researchers who have investigated the crimes of 9/11 now enjoy wider reach than ever before. The battle, although ugly, is certainly not a futile one.

For information on how to support David Miller, visit here.

(Featured Image: “Crowd reflection color toy – Credit to https://homegets.com/” by homegets.com is licensed under CC BY 2.0.)