Recently, I was reading ‘an important paper’ recommended by a philosopher who specialises in epistemology (the study of how we know what we think we know). The paper (Chen et al 2023) investigates the question: ‘Do online platforms facilitate the consumption of potentially harmful content?’ The authors offer what appears to be a rigorous analysis of behavioural and survey data to reveal patterns of exposure to ‘alternative and extremist channel videos on YouTube’. However, they do not explain what they mean by ‘harm’ or ‘potentially harmful’, nor do they give illustrations of the kind of ‘alternative’ content they have in mind. It turns out, in fact, that they take the job of identifying ‘potentially harmful’ content to have already been done for them by NewsGuard, a ‘rating system for news and information websites’. For the authors locate the potential for harm in those channels of communication which, according to NewsGuard, publish information that is not credible.

I found it puzzling that academics should rely on an outside organisation to check the credibility of information that they were prepared to base their own judgements on. One might have expected academics to consider it their own professional responsibility to check the soundness of knowledge claims they rely on, or at least to ascertain the reliability of the methods others have used in doing so. Yet these authors have apparently made no check of the soundness of NewsGuard’s findings or methods; nor do they cite work of any other academic researchers who have done so. Indeed, it turns out, numerous other academic researchers in this field have also relied on NewsGuard without offering any justification for trusting its reliability. It appears that the fact “everyone else does it” has become a self-fulfilling precedent. Nobody cites an authoritative initial source of the precedent itself!

In view of that evident readiness of academics to rely on NewsGuard, this article goes on to examine more carefully what it is that they are relying on. NewsGuard is the name both of a company and its product. One set of questions, accordingly, concerns the general purposes of the company and the people who have set it up, and these are briefly introduced in Section 2. A potential concern arising in this connection is that those behind the organisation all come from senior positions in the U.S. national security state, while the funding for NewsGuard’s journalists comes from entities generally aligned with it. Regarding NewsGuard the product, or service, it is something other than conventional fact checking. As Section 3 shows, NewsGuard offers assessment not of individual items of content but of content providers. The ‘credibility’ assessment provided by NewsGuard relates to a channel of communication or media platform as a whole rather than to any specific items of content it publishes – although NewsGuard makes an exception, as we shall see, for certain hot button topics. Technically, the service operates as ‘middleware’, which is a digital interface that allows service providers to filter content by the application of algorithms designed to apply whatever selection criteria the developers are instructed to deploy. This kind of filtering can, in principle, yield potential benefits for users, but it can also be deployed in ways which restrict users’ access to content that they might have wished to access. Section 4 sets out concerns about the social impact of NewsGuard’s activities, examining evidence of how its filtering can yield problematic results and also serve the ends of government-level actors who aim to suppress critical public debate in the name of ‘fighting disinformation’. Section 5 returns to the concern that originally motivated this article: why are academics choosing to rely on NewsGuard and what are the effects of their doing so? My conclusion is that academics need to become much more alert to the risks of supposedly ‘defending democracy’ by means of censorship — for what is defended in this way would be a democracy in name only.

1. What is the problem for which NewsGuard would be a solution?

In order to check I had not missed something about the rationale or justification for academics like Chen et al to rely on NewsGuard, I looked carefully at how they had established the premises of their research. They indicate that when designating certain YouTube channels as ‘potentially harmful’ they are adopting findings of prior research undertaken by Ledwich and Zaitsev (2020), Lewis (2018), Charles (2020), and an older, highly cited, paper by Stroud (2010). However, they do not provide any summary or overview of what exactly that research relevantly highlights. Having checked these articles myself, I found but one mention of harmful content across the four of them, which is Charles’ reference to white supremacist content. This is relevant to the part of Chen et al’s study which refers to their list of 290 extremist channels, given that the examples they mention do appear to carry some quite obnoxious content — some of it appearing sexist or racist in some sadly familiar ways. So even if they would not be defined as extremist in the sense of advocating terror, violence or insurrection, it might nevertheless be argued that channels promoting sexism and racism are potentially harmful. And I accept that egregiously offensive content of this kind is probably not too difficult to identify.

But that is not the concern animating my inquiry. What remains to be understood is the rationale for also describing as potentially harmful all those channels which are categorised not as extremist but as alternative. According to the typology of Chen and colleagues, ‘alternative channels discuss controversial topics through a lens that attempts to legitimize discredited views by casting them as marginalized viewpoints’. This specification is likely to be tendentious in its application since it raises difficult questions: how to define and identify ‘discredited views’; whose normative judgement is relied on to confirm a view is ‘discredited’; and what justifies the choice of arbiter. These questions go unaddressed by the authors. That this should be regarded as a serious matter I have argued in relation to the work of other ‘disinformation’ researchers like those who have been complicit in U.S. state-sponsored censorship activities (Hayward 2023).

Chen et al do, however, appear to indicate an example of what they have in mind as a channel that attempts to ‘legitimize discredited views’: they mention that ‘the most prominent alternative channel in our typology,’ accounting for 26% of all time spent on alternative channel videos, is that of Joe Rogan. Although they cite no illustration of his show legitimizing any specific discredited view, it does fit their generic categorisation of ‘alternative’ as being outside the mainstream. This classification is uncontroversial if it is applied in the manner of a description to denote channels that are not among the state and corporate media outlets sometimes also referred to as ‘legacy media’. But Chen and colleagues interject a normative criterion: a necessary condition for an outlet to be classified as mainstream is that it will ‘publish credible information’. However, as becomes evident in their discussion, they do not intend this to mean that a mainstream outlet unfailingly publishes credible information. So exactly how or to what extent fulfilment of the condition is necessary remains unclear. Nor do they clarify whether their claim is that alternative media never publish credible information, or even whether they simply do so less than mainstream outlets. To offer any of these clarifications would require the kind of thorough epistemic diligence that they entirely avoid. For we already know that mainstream outlets are not always consistently credible, and sometimes — particularly when they are cheerleading for wars or covering up political scandals — they are not only potentially harmful but actually so.

How, then, do the authors arrive at the inference that the information a channel like Rogan’s puts out is less credible than mainstream outlets? They state that they categorise as a credible media outlet one which has a NewsGuard score greater than 60. Evidently, then, a crucial task — which is the epistemic diligence required to ‘discredit’ a particular view — is outsourced to the NewsGuard organisation. Given that we normally expect academic researchers to do their own epistemic diligence, this degree of trust in a third party business would merit some explanation. However, none is offered. If it had been, then the very basis of their study would have been thrown into question. For if they had carefully studied NewsGuard’s methodology and examples, they would have found, as I shall show, that it provides a very patchy and unreliable guide to the trustworthiness of sources. It does not offer a real solution to the problem of being unsure whom to trust in the sphere of controversial news reporting.

What, then, is the problem that NewsGuard is supposed to provide a solution to? It does not address the problem of a citizen who wants to know how to tell whether any particular report or narrative is reliable or unreliable, for NewsGuard is rating media sources that convey them rather than the quality of the content itself. The problem NewsGuard is evidently designed to solve is that of people taking their news from sources it deems unreliable. People who use sources deprecated by NewsGuard might themselves not experience any problem with doing so. To take the example of Joe Rogan’s show, NewsGuard has actually developed a whole new service — podcast rating — as a direct response to its influential dissemination of perspectives on controversial issues that depart from mainstream orthodoxies. A reason Rogan’s podcast is so influential is that it often features very interesting and well-informed guests responding to serious and thoughtful questions. Listeners evidently find those podcasts can offer worthwhile perspectives on difficult topics that are not typically aired in mainstream media. Having viewed some of the interviews myself, where he asks probing questions and allows full considered answers to be unfolded, I would say that in those instances, at any rate, he is fulfilling a valuable public service. He is ready to ask significant questions that mainstream media studiously avoid.

Of course, this means he often airs views that run counter to those promoted by the security state and big corporations. Perhaps this points to the real problem NewsGuard was created to deal with.

2. Who Are NewsGuard?

NewsGuard is a for-profit company co-founded in 2018 by Steve Brill, a media entrepreneur who has also, for a long time, been a generous supporter of the US Democratic Party, and Louis Gordon Crovitz, whose other positions include being a board member of Business Insider, which has received over $30 million from Washington Post owner Jeff Bezos. According to Whitney Webb (2019), who produced a thorough investigative report on NewsGuard, ‘Crovitz has repeatedly been accused of inserting misinformation into his Wall Street Journal columns, and of “repeatedly getting his facts wrong” on National Security Agency (NSA) surveillance and other issues. Some falsehoods appearing in Crovitz’s work have never been corrected, even when his own sources called him out for misinformation’.

NewsGuard’s advisory board includes senior staffers from the Clinton, Bush and Obama administrations. Among them are General Michael Hayden, a former CIA and NSA director, and Tom Ridge, who, as George W. Bush’s Secretary of Homeland Security, oversaw the implementation of the colour-coding system — like the one adopted by NewsGuard — in the terror threat-level warning system created after 9/11 (Webb 2019). Another is Richard Stengel, formerly Undersecretary of State for Public Diplomacy under President Barack Obama, a position Stengel described as “chief propagandist”, stating he is ‘“not against propaganda. Every country does it and they have to do it to their own population and I don’t necessarily think it’s that awful.”’ (Webb 2019) Others include: Don Baer, former White House communications director and advisor to Bill Clinton and current chairman of both PBS and the influential PR firm Burson Cohn & Wolfe; Elise Jordan, former communications director for the National Security Council and former speech-writer for Condoleezza Rice; and Anders Fogh Rasmussen, a former secretary general of NATO.

NewsGuard has received funding from the US Department of Defense and the Pentagon. One of Newsguard’s most important investors is the Publicis Groupe, the third largest global communications company in the world (Webb 2019), some of whose clients have included pharmaceutical giants Eli Lilly, Merck, Pfizer, and Bayer/Monsanto as well as the governments of Australia and Saudi Arabia (Webb 2019). Another major investor is the Blue Haven Initiative, the “impact investment” fund of the Pritzker family who were the second largest financial contributors to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign (Webb 2019). ‘Other top investors include John McCarter, a long-time executive at U.S. government contractor Booz Allen Hamilton, as well as Thomas Glocer, former CEO of Reuters and a member of the boards of pharmaceutical giant Merck & Co., financial behemoth Morgan Stanley, and the Council on Foreign Relations, as well as a member of the Atlantic Council’s International Advisory Board.’ (Webb 2019) ‘NewsGuard is also backed by the Knight Foundation, a group that receives funding from the Omidyar Network and Democracy Fund, both part of the agglomeration of institutions managed and supported by eBay founder Pierre Omidyar’ (Artyukhina 2019). The Knight Foundation has also been a major funder of the Virality Project and Election Integrity Partnership that were heavily criticised for involvement in censorship (as I recently discussed in a related connection).

In light of the affiliations of their directors, advisors, investors and funders, it is unsurprising to find that NewsGuard consistently gives negative ratings to outlets that tend to be critical of the US establishment and the organisations they are associated with. Critical outlets notably include Consortium News and The Grayzone.

Yet the basis of NewsGuard’s negative ratings can be tendentious or downright false. The case of Consortium News (CN) is one example of manifestly unreasonable assessment. Founded in 1995 by the investigative reporter Robert Parry, CN has published an estimated 27,000 articles. From those nearly three decades of journalism, editor Joe Lauria writes,

NewsGuard found just six articles objectionable because of the use of four words and one phrase. The words are “infested,” “imperialistic,” “coup” and “genocide,” and the phrase is “false flag.” That’s it. NewsGuard has not flagged just those six articles, however. Instead, every Consortium News article going back to the 1990s that can be found on the internet today is condemned with a red mark next to it on search engines and in social media. (Lauria 2022b)

The unreasonable and unwarranted severity of judgement in the case of CN can be contrasted with the leniency shown by NewsGuard towards mainstream sites. Chris Hedges — himself an accomplished journalist formerly writing for mainstream outlets — has highlighted the perversity of some of NewsGuard’s judgements:

‘NewsGuard gives WikiLeaks a red label for “failing” to publish retractions despite admitting that all the information WikiLeaks has published thus far is accurate. What WikiLeaks was supposed to retract remains a mystery. The New York Times and the Washington Post, which shared a Pulitzer in 2018 for reporting that Donald Trump colluded with Vladimir Putin to help sway the 2016 election, a conspiracy theory the Mueller investigation imploded, are awarded perfect scores. These ratings are not about vetting journalism. They are about enforcing conformity.’ (Hedges 2022)

3. What is NewsGuard?

NewsGuard is both the name of a company and of the product/service it sells. The product, which provides the service, can be categorised as middleware. Middleware, in general, is software that lies between an operating system and applications running on it; in this context, it can be thought of as a filtering system that selects what data an internet user’s browser can and cannot access. Middleware has been conceptualised and recommended, in a report from a Stanford working group headed by Francis Fukuyama, as the technological form of a novel solution to ‘countering misinformation’ (Fukuyama et al (2020). They use the term to include ‘software and services that would add an editorial layer between the dominant internet platforms and consumers’ Fukuyama et al (2020). The problem that Fukuyama claimed to have identified was that the algorithms powering the social media platforms cause both social harms and political harms, ‘including threats to democratic discourse and deliberation and, ultimately, to democratic choice in the electoral process.’ In order to counteract such harms, ‘[t]rusted community organizations or preferred media organizations could offer, sponsor, or endorse middleware … that could serve to filter content presented on social media and by search engines, and that would affect news feeds and search results accordingly.’ The authors speak of ‘enormous pressure’ (albeit without elaborating on where it is coming from) for ‘platforms to filter from their domains not just illegal content, but also material that is deemed politically harmful, such as conspiracy theories, fake news, and abusive content.’

As a middleware provider, NewsGuard does not work, as conventional fact-checking organisations generally do, by closely examining particular items of controversial news. It works not at the level of specific stories that might go viral in digital media but, rather, it filters content flows by means of classifying different types of source. As we have seen, it gives a rating to each particular site on the basis of judgements relating to sampled outputs from it. NewsGuard co-founder Crovitz, evidently considers it a merit of this use of middleware that it is not delayed by any effective need to do epistemic diligence on particular stories: ‘Rating websites is more effective than fact checking, which only catches up to falsehoods after they have gone viral.’ Thus, the operative maxim might be characterized as: censor first; ask questions afterwards — if at all.

The reality of the NewsGuard operation, then, is a group of establishment figures, with government funding, working with Big Tech to engage in suppressing any sources of information that tend to publish material that challenges the beliefs they wish to prevail in society. NewsGuard is promoted as providing an effective means of achieving that end. For it can implement various kinds of intervention: it can add labels — such as ‘hate speech’ or ‘unverified’ to platform outputs without removing content; it can also influence rankings for Google searches, Facebook advertisements and YouTube recommendations; and if required it can hide content, or block specific information sources altogether.

Even its promoters are aware that such uses of middleware can have troubling results in the ‘wrong hands’. Fukuyama’s group writes:

In order to ensure that middleware does not facilitate repression, perhaps by autocratic regimes, such services should be opt-in only and designed to prevent censorship.

The problem, though, is that ‘opt-in’ can be exercised by internet service providers, rather than necessarily by individual users, and, more fundamentally, the filters are inherently constructed to engage in activities that can be described as censorship. Although Fukuyama et al emphasise the desirability of a plurality of middleware providers giving users freedom of choice to select the filters that suit their preferences, they offer no reason to suppose that a meaningful plurality is ever likely to eventuate in practice. Moreover, in the unlikely event that meaningful competition were to arise between providers of genuinely different kinds of middleware, and users actually wanted them, then the same ‘problem’ that middleware is supposed to solve could re-appear at the level of regulating what kinds of middleware filter should be permitted. After all, if current audience figures are anything to go by, one might expect many people to opt for a filter that included, say, Joe Rogan rather than CNN. The reality, meanwhile, is that NewsGuard already has a position of dominance, and it has considerable support from the security state — as seen from the composition of its advisory board and the funding being funnelled into it — for further consolidation of that position.

4. The impact of NewsGuard on public debate

There has already been significant uptake of NewsGuard’s services, and NewsGuard’s co-director can boast of some notable successes:

Microsoft was the first technology company to offer our ratings and labels by integrating them into its mobile Edge browser, and providing users of the Edge desktop browser free access. Internet providers such as British Telecom in the U.K., health care systems such as Mt. Sinai in New York and more than 800 public libraries and schools in the U.S. and Europe provide our ratings and labels through access to a browser extension that inserts red or green labels alongside news stories in social media feeds and search results. (Crovitz 2021)

It is also making inroads into universities, since it is provided through the essay checking tool TurnItIn so as to ‘help many million students and teachers spot and avoid misinformation’ (Turnitin 2020). Meanwhile, the evident U.S. Government support for it suggests prospects for its continued expansion.

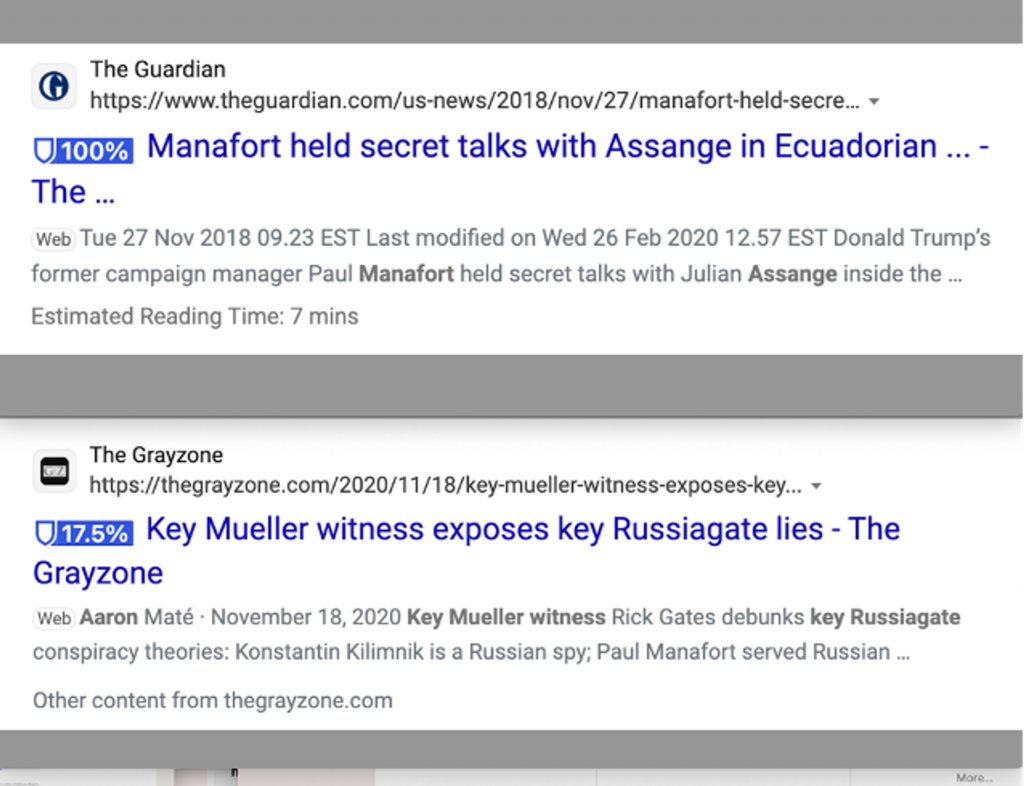

How beneficial the impact of this may be is another matter. A very basic concern is with NewsGuard’s way of presenting its ratings on Microsoft’s Edge browser. For although what it officially claims to rate is a news outlet’s general reliability, the way its results are presented — on the same line and in the same colour as individual titles (see fig. 1) — encourages any casual reader who has not studied NewsGuard’s methodology to believe it is rating the article linked. There is nothing to immediately indicate that the rating actually applies to the site as a whole and that no check at all has been made of the story itself. Accordingly, the casual user may well not realise that every item from a site is effectively either tarred or whitewashed with one brush. So it is that a demonstrably invented and uncorrected story in The Guardian – for instance, about Paul Manafort meeting Julian Assange in the Equadorian Embassy — shows as 100% reliable, while an article exposing such falsehoods in the GrayZone is rated as highly unreliable. This illustrates how readily NewsGuard’s rating system can be so misleading as to invert the truth.

It is obviously problematic to assign a global rating on the basis of a small sample of items, even were that minimal sampling to be carried out scrupulously, fairly and accurately; but, as we saw in the case of Consortium News, NewsGuard is ready to deploy highly selective and unfair sampling to a site that challenges mainstream narratives — hence that site’s unsatisfactory ranking of 47%. But if we look at how NewsGuard arrived at GrayZone’s score of 17.5% (lower even than that of RT — an outlet banned by several platforms and countries — at 20%) we find a deeper problem still.

In rationalizing GrayZone’s bad fail grade, NewsGuard has produced an essay criticizing the site for publishing articles referring to Maidan as a US-backed coup and for its coverage of the OPCW’s investigation of the alleged 2018 chemical attack in Douma, Syria. This sketchy unattributed essay presents highly tendentious treatments of highly contentious complex questions. Specifically regarding the OPCW Douma case, I can comment as a founding member of the Working Group on Syria, Propaganda and Media which has produced several thorough briefing notes on it and was the first recipient of whistleblower documentation concerning it. In my view, the series of articles produced on the topic by Aaron Maté for GrayZone has been thorough and first rate. By contrast, the desultory NewsGuard account simply repeats talking points of UK-US governments based on the OPCW management’s report of the incident and just ignores the subsequent testimony and documents of OPCW scientists who actually did the investigation (an annotated list of which can be found here). These showed that the official report seriously misrepresented their findings, and it is this critical evidence-based material — disregarded by NewsGuard — that the GrayZone’s coverage has highlighted. Championing whistleblowers and holding the powerful to account was regarded as exemplary investigative journalism in the days of WaterGate or the Pentagon Papers but is deprecated today by NewsGuard.

Nor is this an isolated instance of NewsGuard demonstrating a woeful lack of epistemic diligence in arriving at its ratings. Indeed, although NewsGuard officially specialises in rating sources or domains, it acts as a fact-checker pronouncing on the merits of specific claims concerning certain kinds of controversial issue. Notably (and perhaps not surprisingly given the pharmaceutical interests and the military represented on its board of advisers), it has pitched in on issues to do with Covid-19, vaccines, and the war in Ukraine. In 2021, for instance, ‘NewsGuard monitored thousands of news sites, revealing the publication of misleading information about vaccines and political elections’ (Pratelli and Petrocchi 2022). Yet for all its confident declarations of ‘misinformation’ at the time, NewsGuard had afterwards to admit to posting mistaken verdicts. For instance, concerning the origins of the novel coronavirus and the so-called ‘lab leak’ hypothesis, NewsGuard was obliged to affirm that:

… in 21 instances, our language was not as careful as it should have been; in those cases, NewsGuard either mischaracterized the sites’ claims about the lab leak theory, referred to the lab leak as a “conspiracy theory,” or wrongly grouped together unproven claims about the lab leak with the separate, false claim that the COVID-19 virus was man-made without explaining that one claim was unsubstantiated, and the other was false.

Further worth noting here is that even within this particular apparent apology another problematic verdict is reasserted. For although the claim that the virus was manmade might not have been provably true, the fact that the virus could have come from a lab in which viruses were being engineered with gain-of-function technology provided sufficient reason to refrain from categorically pronouncing the claim false. More generally, there is just no reason to suppose that the staff NewsGuard pays have the collective competence to outperform the free exchange of views among actual scientists and practitioners debating such complex and uncertain issues in public forums, including on social media.

What NewsGuard has proved very good at, nevertheless, is reinforcing official narratives. Moreover, its use in libraries, schools and web browsers helps cement those narratives in the public consciousness, along with a perception of their challengers as either fools or knaves. Yet as has been revealed in relation to similar ‘fact checking’ projects in that period, notably the Virality Project, which has been criticised in testimony to the U.S. Congress and is now facing legal action — not least for condemning as disinformation claims that were in fact true — this kind of ‘correction’ too often involved actually reinforcing false claims.

In fact, NewsGuard itself has recently been cited in a lawsuit filed by Consortium News, which seeks an award for defamation and punitive damages for civil rights violations. The complaint asserts that, ‘In direct violation of the First Amendment, the United States of America and NewsGuard … are engaged in a pattern and practice of labelling, stigmatizing and defaming American media organizations that oppose or dissent from American foreign and defense policy ….’ Under an agreement with the Department of Defense Cyber Command, an element of the Intelligence Community, ‘media organizations that challenge or dispute U.S. foreign and defense policy as to Russia and Ukraine are reported to the government by NewsGuard and labelled as “anti-U.S.”, purveyors of Russian “misinformation” and propaganda, publishing “false content” and failing to meet journalistic standards.’ Because NewsGuard’s contract with the government requires it ‘to find trustworthy sources’, there is a violation of the First Amendment which ‘does not permit the government to vet or clear news sources for their reliability, “trustworthiness” or orthodoxy.’

It can accordingly be regarded as a matter of concern that NewsGuard already has a dominant position as a media filter. There seems to be little prospect of what Fukuyama and his colleagues presented in their idealised vision of healthy competition responsive to consumer demand when writing that ‘[a] competitive layer of new companies with transparent algorithms would step in and take over the editorial gateway functions’. They did not explain what would stimulate the competition, nor did their presentation predict just how much government investment would be directed into one specific product. Accordingly, they have given no public consideration to the risk that an entity like NewsGuard might be used by the government as an arms-length tool for censorship efforts that would violate the U.S. First Amendment if implemented by a comparable organisation run directly out of the Department of Homeland Security.

Exactly how unforeseen or undesired this prospect was for Fukuyama is not a question I shall speculate on here, although Mike Benz has emphasised in a series of mini-lectures on Twitter how Fukuyama’s earlier career was in the U.S. State Department’s Office of Policy Coordination, which coordinates with the CIA to ensure that overt and covert foreign policy are synchronised, and which has spawned many of the ‘censorship industry heavyweights’. Fukuyama has since worked at other national security-linked organisations including the RAND Corporation. In his current position at Stanford his colleagues include Alex Stamos and Renee diResta who I introduced in an earlier article.

There is no need to speculate as to intentions, though, because the reality — far removed from Fukuyama’s posited ideal — is that NewsGuard occupies a central position in the development and implementation of government-level plans to ‘fight disinformation’, and not only in the U.S.

NewsGuard has been collaborating in the provision of European Commission data monitoring that ‘tracks online misinformation’ (NewsGuard 2022x), and is one of the companies involved in the Commission’s revision of its Code of Practice on Disinformation for social media platforms (NewsGuard 2021). The tactics to be deployed in this ‘information war’ are not restricted to flagging deprecated outlets; they also crucially include choking off funding to them, in particular by targeting their advertising revenues.

In announcing planned revisions to strengthen the code, Věra Jourová, European Commission Vice-President for Values and Transparency, said: “Online players have a special responsibility regarding spreading and monetizing disinformation.” (NewsGuard 2021)

The European Commission has presented its Code as the first ‘framework worldwide setting out commitments by platforms and industry to fight disinformation.’ (European Commission 2021) Indeed, the German Marshall Fund (GMF) had already proposed cooperation between the US and Europe that specifically would target funding streams with the goal of ‘changing Internet platforms’ incentives-setting’ (GMF Experts 2021).)

In fact, a week after the European Commission updated its Code, the ‘Global Alliance for Responsible Media (GARM), an initiative created by the World Federation of Advertisers to promote responsible advertising practices, announced for the first time that it had added “misinformation” to the list of online harms it deems inappropriate for advertising support. GARM’s previous standards, relating to issues such as pornography and violence, have been widely adopted by the industry.’ (NewsGuard 2022) These new global standards ‘compel brands and ad tech companies to stop $2.6 billion in advertising on misinformation’ (NewsGuard 2022) NewsGuard has been active in seeking to ‘accelerate compliance’ with these GARM requirements ‘to address the $2.6 billion industry of ad-supported misinformation’ (NewsGuard 2022) Moreover, these new standards are only the beginning, according to co-CEO Brill, who believes ‘the enactment of further regulations on this topic is all but inevitable.”’ (NewsGuard 2022)

NewsGuard now stands as an integral part of a monolithic system of information control that former State Department staffer Mike Benz has depicted as the censorship industry:

‘From 2006 to 2016, censorship was an act. In the five years that followed, censorship became an industry. Its powerful stakeholders now span every major media conglomerate, every major online payment provider, every major US and UK college and university, hundreds of think tanks, NGOs and pressure groups, international regulatory and watchdog commissions, and is now firmly interwoven with the policies and operations of the US State Department, the Pentagon, and the intelligence services.’ (Benz 2022)

The present study of NewsGuard’s aims, methods and achievements – in conjunction with my earlier look at connected ventures such as Election Integrity Partnership and Virality Project – suggests very good reason for public concern that ‘fighting disinformation’ is really just about preventing opinions disapproved of by global corporate state players from being widely heard.

5. Impact on Academia

One might expect informed observers to be concerned about this surge in censorship, especially given its contestable basis; and one might have expected academics to be at the forefront of articulating that informed concern. For free communication is essential for the conduct of science and scholarship. Sadly, such expectations are far from what has materialised. Those academics who are aware of NewsGuard’s existence, instead of being critically attentive to the risks it brings, are mostly looking to it as a provider of a service that allows them to investigate patterns of ‘misinformation’ or ‘disinformation’ without themselves having ever to do any epistemic diligence on the content so deprecated. The impact of NewsGuard on academic thinking is indicated by Google Scholar returning 940 entries with NewsGuard as the search term (as at 27 September 2023). An informal survey of this literature suggests that the preponderance of articles returned are concerned with the algorithmic identification of ‘misinformation’ using source site as a proxy for it. So although NewsGuard does not claim to assess articles individually, its blanket verdicts for sources are generally treated as doing something substantially similar. Indeed, some academics refer to it as a fact checker (e.g. Sharma et al 2020). One presumption encouraged by NewsGuard’s approach is that an article from a red-flagged site is likely to be unreliable whereas an article from a green-flagged site will generally be reliable. Zhou et al are even ready to assume that ‘NewsGuard has provided ground truth for the construction of news datasets … for studying misinformation.’ Zhou et al (2020, 3207)

A remarkable number of academic researchers are content to base projects on NewsGuard’s ratings. The justification most typically given for doing so is that there is precedent for it in the academic literature. Broniatowski et al (2022) note the assumption is widespread in prior work and they cite six examples of articles premised on it. Typical is Lasser et al (2022) who explain that they assess the trustworthiness of politicians’ tweets by checking the NewsGuard rating of the domains they link to. In doing so they state that they are ‘[f]ollowing the methods of prominent research concerned with the trustworthiness of information’. They are also typical in not providing any reference to a basis of explanation or justification upon which the precedent was established. In fact, so far removed are some researchers in this area of inquiry from any sense that actual epistemic diligence could be important that there is even a suggestion that the kind of credibility rating NewsGuard engages in could be more fully automated (see e.g. Aker et al).

Furthermore, it is not only the site or domain level ratings that some academics are ready to rely on. As was earlier noted, on certain controversial issues, substantive judgements about specific contents are prominently promoted by NewsGuard. Given the shaky basis and inherently problematic nature of these verdicts, it is a further concern to find them sometimes uncritically accepted and amplified in academic publications. For instance, Zhou et al (2020), in a paper already cited 170 times by 26 Sept 2023, states as fact that ‘[h]undreds of news websites have contributed to publishing false coronavirus information’, where the reference for this claim is this NewsGuard page, which, as shown earlier, is replete with controversial and even erroneous assertions.

In short, there is reason to think the effect of NewsGuard on academia is deleterious – not only for academia but also for the wider society. But it is academics themselves who have allowed this effect to be exerted. The reasons for its embrace are not far to seek: a great deal of funding is being pumped into ‘disinformation research’ that follows the required agenda of those disbursing the funds. How this works has already been illustrated in my related recent study of Academic Complicity in Censorship: the Case of Kate Starbird. There is sadly little reason to suppose this trend will be reversed in the near future. But it remains possible for academics who still are able to able to engage in more generally independent research to heighten awareness at least among ‘third party’ colleagues — like the philosopher who set me on this inquiry, for instance — of the Faustian bargain that others in our community have accepted.

Conclusion

Censorship is rapidly becoming normalised. Former protections for freedom of thought and expression, as well as guarantees for academic freedom, are becoming increasingly hedged and marginalised. New entities like NewsGuard are promoted as providing protection for citizens — and also even for academic communities — from what we are told are dangers and harms of disinformation. But the real danger is that as our opportunities to share ideas and learn different ways of seeing things will be increasingly curtailed and leave us unprotected against the monolithic imposition of officially ordained ‘truth’ that NewsGuard is already playing a significant part in achieving.

Who is on guard to protect us from NewsGuard’s ‘protection’? Given the position of universities in the social division of epistemic labour, one would expect academics to be critically scrutinising its methods and findings. Yet, as indicated here, academics at present seem mostly to be asleep on the job — or to have accepted the incentive provided by lavish “disinformation research” funding to look the other way. It therefore seems that we, as citizens, will have to do the neglected epistemic diligence ourselves by critically discussing what it is doing and how to resist it while we still have meaningful opportunities to do so.

(Featured Image: “Hand holds a piece of paper with text fake over fact text. Fake or Fact concepts” by wuestenigel is licensed under CC BY 2.0.)